In this email interview, Harada Maha discusses her novel Applause, which she published on her official Twitter account and “Maha’s Gallery,” her official Instagram page, over a period of 18 days.

What made you decide to publish Applause as a serialized novel via social media? The “I” in the story seems to be the real you, as if it’s a kind of autobiographical novel. Why did you decide to publish your thoughts in the form of a novel rather than simply expressing them on Twitter?

One of my bases is in Paris, and I often travel back and forth between Tokyo and Paris. Whenever I go there, some amazing exhibition is going on, and it gives me a chance to compile as much information as I like. Over these last five or six years, I’ve written a succession of art novels that are set in Paris.

This year an exhibition of unprecedented size was held at the Louvre to commemorate the 500th anniversary of Leonardo da Vinci’s death. I arrived in Paris just in time, on the very last day of the show [Feb. 24]. It was extremely crowded and there was a great deal of excitement in the air. Thinking back on it now, I realize that it satisfied all three of the conditions that facilitate the spread of the virus. It was a closed space with a large crowd of people in very close contact with each other. I looked at the exhibition pressed right up against the faces of many French and Italian people. Amazingly, I was the only Asian there. That was right around the time when the novel coronavirus was raging through China, and starting to be a problem in Japan after a cluster of cases was discovered on a luxury cruise ship. There was absolutely no sense of danger in Paris. The pandemic was something that was happening in some far-off land. If someone had suggested that the city would be in lockdown in three weeks’ time, everyone would have looked at them like they were crazy. But it seemed very weird to me that I was the sole Asian at the Leonardo exhibition. For all of the tons of Asian tourists in town to suddenly vanish made me think that the situation must be quite grave.

Not long after, the number of infected people in Italy began to rise, and in the first week of March, news reports on the virus became a daily occurrence in France. I suddenly had a premonition that before long the museums would close, so I went to the Louvre on the last day of February. I had the feeling that I was being called there by a Mesopotamian jar (“the oldest item in the museum’s collection”), which I had come across ten years earlier, and posted a picture of it on Instagram. Then, the very next day, the museum closed. That’s when I knew that this was no laughing matter.

The entire city was locked down two weeks later, and I realized that I had inadvertently become the parties concerned and was now witnessing a historic event. In my books, Guernica Cover Up and The Dreamer’s Collection, I wrote about the historic moment when, in 1940, the Nazis invaded Paris and began to occupy the city. Sensing that what I was witnessing was on a par with those events, I decided I would try to document the situation in my own way, and that led me to the idea of writing a novel in real-time. I thought about just making comments on Twitter, but the social media format is one in which something of immediate importance is posted and then disappears. The fact that things don’t remain is a good thing, and that’s very different from a novel. I thought that as a writer I wanted to convey the realities that I saw, and as a witness I wanted to record history.

This explains why people all over the world are currently re-reading Camus’ The Plague. While sharing this moment with readers, I also wanted to send a message to people in the post-corona era. That was my primary motivation for writing Applause.

Even though your readers knew that the last installment of the novel wasn’t that far off, it was interesting to see what kind of thing you wrote about every day. Many readers were also very concerned about your personal condition during the lockdown in Paris.

The reason I decided to limit the series to 18 days was based on the foreword I posted on March 29, the day before I started writing it.

On March 29, there were 1,827 people with the virus in Japan, and 37,575 in France. Eighteen days earlier, the number in France had been 1,784.

In other words, as of that day, the number of cases in Japan was about the same as it had been in France 18 days earlier [March 11]. On March 11, no one in France could ever have imagined that a lockdown might take place. This meant that if Japan didn’t take immediate action, it had the potential to become the same as France in 18 days. I wanted to sound the alarm.

March 29, the day I decided to write Applause, was the day that I found out about the comedian Ken Shimura's death. Shimura had been set to appear in the film version of my book The God of Cinema. It was also the day that I made up my mind to return to Japan. Honestly speaking, I had no idea what was going to happen to me in 18 days’ time. Would I really be able to go back? What would happen if I tested positive after I got back? I had seen some reports about the thoughtless way that people were treated after they went back to Japan. I felt anxious and scared. But I invested a glimmer of hope in that 18-day series. During that time, I hoped that Japan might change course, that someone might come up with a way of containing the infection, and that all of us would reach an understanding and cooperate in overcoming this terrible virus.

It was immediately clear that containment would not be possible, but I still thought we might attain some new knowledge at the last minute. And as it happened, many Japanese found themselves boxed into a corner, and realized what they had to do. With a sense of collective responsibility, they began to make a unified effort. Now, almost everyone wears a mask in urban areas, and as I understand it, a considerable number of people have cut down their contact with other people by 70 or 80 percent. The number of virus cases for the 18-day period from March 29 to April 17 was 9,220. Approximately five times the number it had been prior to that. The number is increasing, but it is still amazingly low compared to France. In France, after the 18-day period that began on March 11, the number of cases skyrocketed 21-fold. I have no idea why the difference is so great, but things like Japanese people’s awareness and seriousness, and their innate attitude toward public hygiene are very different from those of Western people. I wrote about this in “Day 17”: “Never speaking in the presence of others…. That is one of Japanese people’s strengths.” In other words, because we don’t talk in front of people, we don’t spray droplets of saliva when we meet each other. It’s completely different in the West. Western people converse in loud voices and don’t see anything wrong with asserting themselves. On the other hand, Japanese people have the reputation of being passive and quiet. Some people might ask why it is that we don’t express our thoughts. In normal times, that could definitely be seen as a weakness. But in the pandemic, this has instead come to be seen as a strength.

In reconsidering the differences between Japanese and Western culture and customs, we see that in Japan there is a sense of shame associated with appearing in public and in front of other people. This sensibility is much stronger in Japanese people than it is in Western people. Personally, I believe that this proved to be very advantageous in the pandemic.

I realize that many people were very concerned about whether I was able to return safely from Paris. But since I was working in the novel format, I’m afraid that coming out and saying that I had returned at the end was not really an option. At the same time, I was deeply grateful for all of the real-time responses I received from readers.

You were staying in Paris at the time of the lockdown, and things there were completely different around that time from the way they were after a state of emergency was declared in Japan. What kind of emotions did you feel after Paris, normally such a vibrant city, underwent such a huge change? Were you surprised? Afraid?

It all started so suddenly that the main thing I felt was surprise [Day 5]. I was surprised at France’s latent ability to “cross that bridge when we come to it,” but France is also a country in which the people endlessly assert their democratic and sovereign rights. Instead of moving forward with lightning speed and power, it is essential to be properly compensated. Otherwise, there was no way people would agree to remain silent and stay at home. I became acutely aware of how different the French social structure is from Japan’s, and that France is a strongly democratic country.

Despite the fact that you have traveled all over the world, this was probably the first time that you had ever faced the prospect of not being able to return to Japan. Amid the constantly fluctuating situation in Paris, what kind of things were you worried about and how did you overcome them?

When I walked through the city during lockdown, it was indescribably beautiful. It was exactly like being on a movie set. But at the same time, I felt dispirited and empty [Day 7]. It made me realize how truly human Paris is. When Paris is lively and filled with people, it brings out the beauty of the city.

Although I thought that I would be able to concentrate on my work and simply retreat into my own world, I actually felt flustered and helpless, and all I could think about was washing my hands [Day 11]. When I began to realize that I might not be able to return to Japan, I grew strangely sentimental and resigned myself to facing whatever lay in store in beautiful Paris [Day 12]. What completely changed things was the news that Ken Shimura had died.

Somehow the idea that someone like Shimura, who was beloved by so many people, lost his life to the virus and was forced to set out on his final journey without anyone there to see him off, made a huge impact on me. There were parallels between his situation and mine. If things became grave, and the medical system was on the verge of collapse, I might have to impinge on the kindness of my French friends. If I ended up dying, I had no idea where I would be buried, and I would disappoint my family and associates in Japan as well as all of my readers. It was impossible for me to take responsibility for myself in this situation. When I realized that, I decided it was time to go back to Japan [Day 14]. At the very least, I would be able to look after myself there. Under the circumstances that was all I could do.

In the end, I was motivated by Shimura’s premature death. I never actually met him, but according to the director Yoji Yamada, Shimura was a “comic genius.” I’m sure that he was a truly great person.

It was vital that his death did not go to waste. As I see it, Shimura’s passing was the ultimate warning to Japanese people that we should not underestimate the pandemic. After he died, there truly was a dramatic shift in people’s awareness, including that of the government.

When I realized what the connection was between the title Applause and the story, I was deeply moved. Was it your intention to convey a sense of hope through the story?

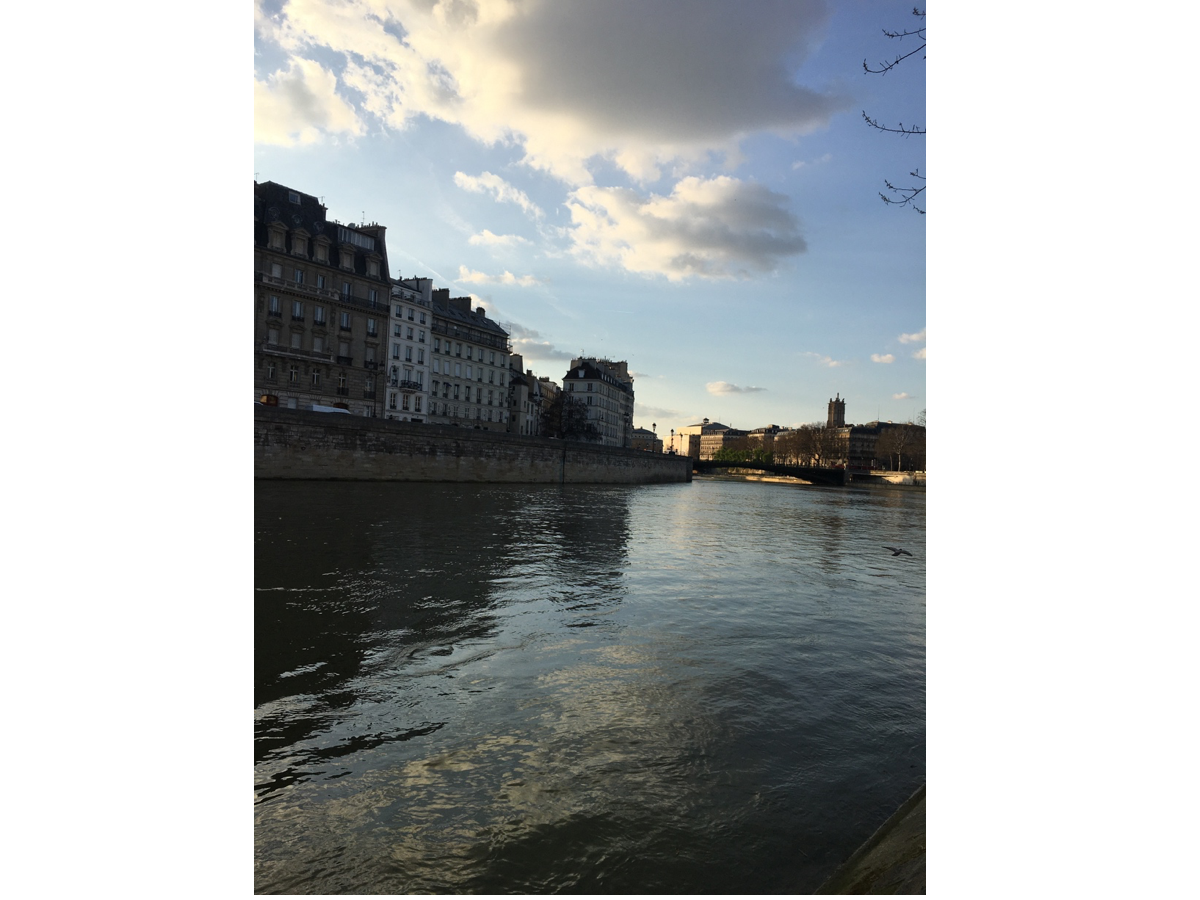

Not long after the lockdown started, people would step out on their balconies at exactly 8:00PM and break into a round of applause to express their gratitude for medical workers. This practice spread through the city spontaneously. My study faces the Seine, and just as the evening chime rang at 8:00PM, I would hear the wave-like sound of people clapping. I started opening my window and joining in too [Day 16]. The applause was a display of gratitude to the health professionals who were risking their lives for us, but at the same time it seemed like a proof of life – an expression of determination by people throughout Paris to show their solidarity and say, “We’re alive. Everybody is in this together, and we will survive!” There was nothing quite as moving as the sound of that applause reverberating through the empty city and along the flowing Seine. It made a deep impression on me. I became firmly committed to recording this experience in my writing so that it wouldn’t be forgotten. The first thing I came up with was the title.

Alongside the story, you posted beautiful pictures of Paris and paintings. Were these pictures that you had taken in the past or ones that you took during the lockdown?

They were all taken in Paris during the lockdown. The sight of Paris without a soul on the street was extremely beautiful, but it was also a desolate scene. All economic activity had ground to a halt, the noise was gone, the air had cleared up, and the sky was blue. The expansive sunset looked like a painting. It all seemed very ironic.

There are also two pictures of works by Leonardo [Day 9 and Day 14]. Unlike the rest of them, I took these on February 24 at the Louvre exhibition. Leonardo drew The drapery of the Virgin's thigh when he was in his 20s. It is a small 30-cm-square drawing, but there is something inexplicably overwhelming about it. First of all, it’s amazing to think that a nameless youth of only 20 or so drew it some 550 years ago. But what’s even more amazing is that it was preserved and conveyed from person to person over those 550 years, and that after 550 years, it has retained the power to move people who see it today. This small picture drawn on a piece of paper is a testament to the fact that the essential nature of human beings remains unchanged. The existence of the picture encouraged me and made me realize how important it is for creators to survive and leave something in other people’s hearts.

Maha visited the Picasso Museum just before the COVID-19 lockdown. There were no other visitors, unlike a typical day, and there was not a soul in sight in any of the exhibition rooms.

Even though we intellectually understood the importance of secluding ourselves to fight against the novel coronavirus, it proved to be quite difficult to keep our distance from other people and shut ourselves away. But seclusion is a way of protecting yourself as well as other people and the rest of the world. Could you share your thoughts about this?

With each passing day, we have come to understand more about how the virus spreads. We now know that droplets of saliva are the primary source of infection, and things like wearing a mask, staying 1.5 to two meters away from other people (social distancing), and avoiding the three Cs (closed spaces, crowds, and close contact) have gradually become common practice. More than that, trying not to meet people, refraining from talking when you do meet someone, and intentionally shutting yourself away are ultimately the best things you can do to protect yourself and others. We have also come to understand that this is the only possible way to end the pandemic.

What makes this virus so cunning is its ability to infect people during the incubation period and without producing any symptoms. It’s natural to stay home and rest if you have a fever or a cough, but when there’s nothing out of the ordinary and you make regular contact with people, the infection spreads rapidly, and people with a history of illness or a chronic disease, and weaker people such as the elderly run the risk of serious consequences – despite the fact that the carrier has no idea what’s happening. That’s what makes it such a horrendous disease.

This explains why so many countries have enacted strict lockdowns. But when a government simply forbids people from going out and forces shops and companies to close without providing them with any compensation, it goes without saying that people are going to disobey the rules. When the risk of losing your livelihood becomes greater than the risk of suppressing the virus, what’s the point? That’s why most countries offer compensation as part of a package with the lockdown. The Japanese government, however, lacked to resolve this. They were unwilling to provide 100-percent compensation or to take responsibility, so the only thing they could do was to ask people to voluntarily restrain themselves. From the get-go, it was just a bunch of shilly-shallying. No wonder people are angry.

I paid close attention to the statements various world leaders made before and after the lockdowns. It was German Chancellor Merkel’s touching speech and policy that received the most support from the people while also proving to be the most effective means of stopping the spread of the virus. A Japanese translator [Mikako Hayashi-Husel] translated Merkel’s speech in real-time and posted it on her website, so I had a chance to read it the very next day. The speech conveyed Merkel’s outstanding qualities as a leader, and I was also impressed by the translator’s sensitivity, and her sense of mission to quickly translate the speech and share it with people. I intuitively sensed that as a Japanese person living in Germany she felt a need to alert Japanese people to the speech. Knowing that there are bright people like her out there who provide the underlying support for communication was very encouraging.

You mentioned that now more than ever is the time for people to read your book Tossed but never Sunk. What would you like to convey to people in this period of self-restraint with this book?

During the lockdown in Paris, I stared out of my window at the flowing Seine every day, and on my once-daily outings, I would also gaze down at the river from the bridge. As I did, I would think about Van Gogh’s lonely life. There’s no question that he continually struggled with loneliness throughout his spectacular life. But at the same time, he was brave enough to face it head on. This is borne out by the fact that the paintings he made during the last year of his life, after the world had completely passed him by and he was at his lowest ebb, are his most outstanding works.

The lesson of Van Gogh’s works is that when an artist is completely alone, they come face to face with themselves and hone their sensitivity. But it isn’t until someone else looks at what an artist made as a result of their loneliness that it becomes a work of art. The same goes for every kind of art, whether it’s a novel, a musical composition or a theatre piece. An artist may send out their creations, but until there is someone else there to receive them, they are not art.

In Van Gogh’s case, it was his younger brother Theo who fulfilled that role. His brother could never have imagined that 100 years later Van Gogh’s works would continue to be loved by people all over the world. Like a little boat rocked by rough seas in the middle of a storm, they were swallowed up by the waves and died. But eventually, after the storm subsided, Van Gogh’s works surfaced between the waves and were accepted by the world. The title Tossed but never Sunk (Fluctuat nec mergitur) [Latin for “the vessel is rocked by the waves but she does not sink”] alludes to the Van Gogh brothers’ success after they had laid their lives on the line.

The phrase is the motto of Paris and it appears on the city’s coat of arms. In ancient times, the Seine, which flows through the center of Paris, often flooded, creating many problems for sailors. The sailors, though, would compare themselves to Île de la Cité, an island in the middle of the Seine, saying, “In a storm, the island sometimes vanishes after it is submerged in the waves and rocked like a boat. Once the storm passes, however, the island reappears. Paris is like the island. It may be rocked, but it never sinks.” The sailors also painted this phrase on the bows of their ships as a good-luck charm.

When the rough seas of a particular era surge, we may be rocked, but we do not sink. Now, as the waves cover us, is a time for self-possession and patience. Once the storm has passed, we will remerge from the waves and continue on with our journey. That’s why I thought it was important for people to read my book and keep that phrase in mind.

I’ve heard that bookstores are still in business and that now more than ever people are buying books. What sort of attitude do you think is necessary at this point when the need for self-restraint shows no signs of abating?

During the lockdown when I contacted my older brother [the writer Munenori Harada], he said, “All I have to do to save the human race is sleep.” That sounded like him all right. [laughs]

In the past, I declared that my hobby was “moving around,” and I was always rushing around without enough time. But now I can move around at my leisure and spend time enjoying writing, reading, and cooking.

I find not being able to go to the museum or travel incredibly sad. But this is not going to continue forever, and I’m not the only one who has to deal with it. Everyone in the world has to endure this situation for a while. We have to hold out and accept the fact that it’s going to take a while longer, and it’s vital that we take care of ourselves and avoid catching the virus to help ensure that the medical system does not collapse. As far as what you can do to boost your immune system and protect yourself against the virus, eating a balanced diet, getting plenty of sleep, and keeping regular hours are probably the best bet.

Research also suggests that enjoying art, music, and theatre is an effective way of strengthening your immune system. Until the day comes when it is possible to completely enjoy the fine arts in a post-covid world, this seems like a perfect opportunity to cultivate your knowledge by looking at paintings, watching movies, and reading books in preparation.

The idea that we can help save the human race by taking it easy at home is a wonderful one. The Renaissance began after the Black Plague subsided in Europe. I hope people will take this chance to remind themselves how wonderful it is to live a normal human life, and to be more considerate of themselves and others to enable all of us to survive. As one of the people living in this world, I am committed to staying alive, continuing to write, and expressing myself.

Translated by Christopher Stephens

© 2022 Maha Harada