Two years have passed since Maha Harada published the novel Applause on Twitter in the midst of being locked down in Paris. In this first part of the interview, Harada discusses her serial novel Homesick, which she began publishing on March 17 for a period of 18 days.

Applause placed a strong emphasis on surviving and leaving something for the future.

The other day you posted the final installment of the serial novel Homesick, which was published over 18 days on Twitter. I read the book in these daily postings. Two years ago you wrote Applause in a similar way from the time that you were in Paris until the time that you came home.

During the Paris lockdown, I was forced to seclude myself in my apartment. That was when I started to think, Maybe I’m experiencing something that I will never experience again for the rest of my life. I’m a writer, so I wouldn’t go so far as to say that I’m a witness to history, but I had the feeling that I should record what was happening in order to document history. Rather than evoking certain people and things in a novel, and arousing certain kinds of thoughts, I became fixated on leaving something behind as a writer.

As a student of art history, I knew that historical turning points are closely linked to always keeping your eyes peeled. Ten, fifty or a hundred years from now, people will undoubtedly want to find out what happened at a given time. My primary motivation was sharing my feelings with people who are now living, but I was also strongly aware of preserving something for the future.

In Applause, you wrote, “All of the windows along the river were open, and everyone was applauding all at once. People were expressing their gratitude for the healthcare professionals who had laid their lives on the line and continued to work. I joined them in sending out my heartfelt appreciation.” After reading the book, I felt that it contained a strong message about survival.

Healthcare workers did their utmost to save the lives of people they were dealing with, but the situation was so overwhelming that their own lives were at risk. One thing the people of Paris could do to convey their appreciation was to applaud the workers’ efforts. It wasn’t as if someone had announced their intention to do this. One day the applause just started spontaneously, and to me it seemed like a symbol of hope for the future. I will never forget sending out applause into the madder-colored sky. I am strongly aware of the fact that that was then, and now is now.

Neither I nor anyone else has the ability to predict what is going to happen tomorrow.

You decided to publish the novel over a period of 18 days on Twitter. Was there any special reason for that?

At the time, I had no idea what might happen tomorrow or in a few days, so it was completely impossible to imagine how things would be in 18 days. Until the day before, shooting on the film The God of Cinema was going ahead as planned, but the following day I suddenly heard that the star of the movie, Ken Shimura, had died. I had originally planned to stay in Paris for a while, but the day after I heard that Shimura had died, I decided to return to Japan. I had the feeling that my luck could run out any day.

Looking back at the long history of humankind, one day seems like any other day, but some days prove to be big turning points for some people, and those days might also change history.

When I consider time, I think that the moment in which I am living is merely a succession of “nows.” It always seems so strange the way that time passes and “now” vanishes. When I try to imagine where I will be in the future, I realize that no has the power to predict what will happen in the future.

On February 24, Russia invaded Ukraine. As you learned more about the war from news reports, did you feel the need to take some kind of action?

I thought about how I had written Applause in Paris exactly two years earlier. The situation in Ukraine changes with each passing moment, leading to new earth-shaking threats. In a sense, the war is also connected to the lockdown that occurred two years earlier.

As I wrote in Homesick, Japan is 5,000 kilos away from Ukraine and 2,000 kilos away from France. But what do these distances really mean? As I wrote in Applause, it is important to keep a close eye on how people in Paris, some 2,000 kilos away from Ukraine, react and what happens there. I have a variety of concerns related to whether or not I should go to Paris under the present conditions, but there are unquestionably things that need to be documented there. When I set off on a journey, I take all of these things into account.

Watching Parisians wait with bated breath as the situation in Ukraine changed minute by minute filled me with an eerie sense of calm.

What did you think when you first heard that Russia had invaded Ukraine?

Today, there are a number of very dangerous situations around the world in which a certain group is attempting to create a country based on its own set of rules. This is not only true in Europe, but also in places like Myanmar, where the military government seized power in a coup. Despite this, I never imagined that something as anachronistic as invading another country would occur in the 21st century.

I have been following the news in Ukraine very closely. The process that led from the collapse of the Soviet Union to the invasion of Ukraine is extremely complicated. There is something discomforting about the thought that another country would come up with an idea of this kind. But it’s also unfortunate that the rest of the world was unable to come up with a stronger proposal for stopping the war when they negotiated with Russia in February.

When you arrived in Paris on March 5, what was happening there?

France was moving ahead much faster than Japan to administer the third dose of the vaccine, and since many of the people who contracted the Omicron variant were only experiencing minor symptoms, an exit strategy for the coronavirus had begun to take shape. Tourists were also starting to come back a little, and even though the numbers were not as high as they had been before the virus, there were tons of people waiting outside the Louvre to see the Mona Lisa.

I felt a sense of freedom after having been locked up for two years. On the other hand, there was an endless stream of news stories about the situation in Ukraine, and I also witnessed people in Paris who had lost their homes and were covered with cuts and bruises. But watching Parisians wait with bated breath as the situation in Ukraine changed minute by minute filled me with an eerie sense of calm. I struggled for a way of dealing with the gap between these two different realities.

As I understand it, you already had the title Applause before you started to write the book. How was it with Homesick?

I decided on that title before I started writing that book too. Everyone, no matter who they are or where in the world they were born, feels homesick for some place. It filled my heart with pain when I thought about what it must mean to lose your homeland, as those five-million Ukrainians fled their country to escape the war.

There are three things that people should never be deprived of under any circumstances: life, liberty, homeland. These three things are normally things that no one should or could deprive us of, but in Ukraine, that is exactly what is happening. It is difficult to comprehend why adult human beings would shamelessly attempt to do something that even a child knows is wrong.

At the very least, regular people have the ability to make an effort and study, turn over a new leaf, and change their own future. But with emergencies like the virus, you are confronted with the fact that no matter how much you want to, there is no way to deal with the situation. Realizing this, I was left with feeling very perplexed.

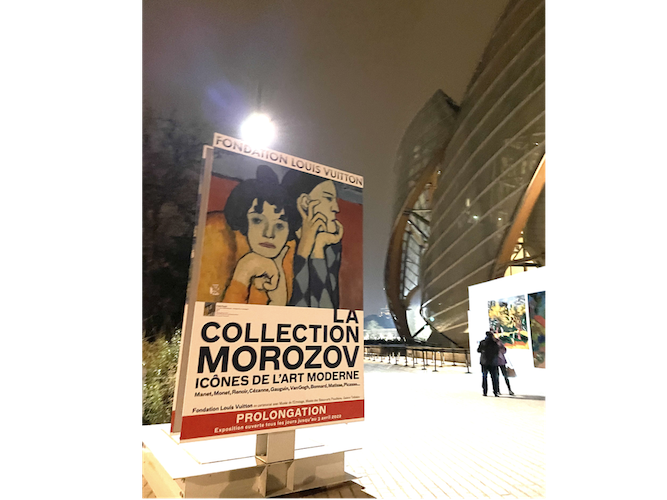

In Homesick, you talk about the Morozov Collection exhibition that was sponsored by the Fondation Louis Vuitton.

The Morozov Collection was amassed by the Morozov brothers, two Russian businessmen, between the late 19th and early 20th century. Many of the works that they collected were made by French artists, and the brothers took them back to Russia. After the older brother, Mikhail, died, the Russian Revolution occurred, so the younger brother, Ivan, defected to Switzerland and the government confiscated the collection. Ivan never had a chance to return to his homeland or to see any of the artworks he had worked so hard to collect. Filled with nostalgia for the past, he died in exile. The history of the Morozov Collection is one in which two Russians took a group of works by French artists back to their homeland, but in the end, the government appropriated them as national properties.

That was why you used the word “homecoming” when you described the exhibition in Paris, right?

In the past, the collection was divided between two museums, one in Moscow and the other in St. Petersburg, and all of the works had never been assembled in a single place. For this homecoming exhibition, some 200 works were selected from the collection and gathered together.

As I was looking at the Morozov Collection, I started to wonder who the works actually belong to. In Homesick, I wanted to consider issues such as life, freedom, and homeland, the three things that no one should ever trample on, and who these artworks belonged to.

I had the intuitive feeling that the Morozov Collection might not ever return.

You quickly went to see the Morozov Collection exhibition immediately after it opened in Paris in late September last year, right?

I went once in October, and at that time it was scheduled to run until the end of February 2022. But I was surprised to learn that the exhibition had been extended soon after I arrived in Paris. Popular exhibitions are often extended, but usually once the exhibition is over, the works are returned to the owner as soon as possible.

You mean, the museum that borrowed the works quickly returns them?

Since they have to pay insurance for every extra day, as soon as the exhibition is over, the museum quickly checks the condition of the works and sends them back. In a case like this in which the collection has such a high concentration of amazing works, it’s even more difficult because they are usually divided up and flown back using a few different airplanes. When I heard that the exhibition had been extended, I thought perhaps the works were not going to be returned; I intuitively thought that the French government might decide not to send them back.

As you mentioned on Twitter in a kind of sequel to your novel Homesick, your hunch was correct, and they did decide not to return the works that were owned by Russian oligarchs and the Ukrainian museums.

When I wrote The Dreamer’s Collection, which deals with the Matsukata Collection, I thought very deeply about the fate of paintings that become entangled in a war. Although our way of dealing with culture is more civilized now than it was then, the question is, Where is the best place for the works to be kept? There is always a risk of becoming embroiled in a war, and there is no guarantee that important artworks won’t be subjected to vandalism. There haven’t been any official statements regarding the works in Russian museum collections and modern Impressionist masterpieces, but showing publicly runs the risk of sparking a culture war.

The catalogue for the Morozov exhibition included a statement from President Putin.

Historically, in times of peace, art and artworks have often functioned as ambassadors for cultural exchange. But in a state of emergency, those in power immediately forget about culture. From here on out, it’s going to be difficult for other countries to borrow works from Russian museums, and we will also have fewer opportunities to visit Russian museums.

I’ve been to Russia three times or so, and while I was there, I visited the Tolstoy Museum and the Pushkin Museum. I told the head curator at the Tolstoy that I was a Japanese writer with a deep reverence for Tolstoy and asked if she would show me one of his manuscripts. She said that she would show me one of Russia’s national treasures, the manuscript of War and Peace. As she watched me staring intently at the pages, which were covered with so much beautiful writing that there almost no margins left, I had the sense that it struck a deep chord with her because she kept saying, “This is one of our national treasures,” over and over again. The curator at the Pushkin also explained the works with a great deal of pride. It makes me sad to think about the people I met on that trip.

In a completely empty gallery, I had a premonition that this might be the last farewell.

The Morozov exhibition took on a completely different meaning after the war in Ukraine started.

At the end of the exhibition, there was a Van Gogh work called The Exercise Yard, or The Convict Prison, which was carefully guarded. Van Gogh made this painting after he was committed to a mental asylum, which meant that he was no longer allowed to move around freely. Being separated from his birthplace in Holland and his brother Theo, who was in Paris, Van Gogh experienced a kind of homesickness. As I had a chance to stand in front of the painting all alone just before the museum closed, I felt as if I could hear Van Gogh screaming, “I want to be free!” and “I want to go home!”

In many cases, I feel a spring in my step after I look at an outstanding work, but as I walked away from that painting, I immediately had the sensation that I was leaving one of my own blood relations or siblings, so I impulsively took a photograph of it (Day 18, Homesick). The fact that this feeling continued unabated made me think that I might never see the painting again in my life.

Did you ever have that kind of feeling in the past?

That was the first time I ever felt as if I would never see a work again after I left the museum. As long as I live, I hope to visit many more museums and see many more stunning masterpieces. But in that completely empty gallery, I had a premonition that that might be the last farewell.

Unfortunately, it looks as if it will be a long time before we reestablish diplomatic relations with Russia. I still haven’t found the answer to that big question that I posed in Homesick. Having felt the need to write about what was going on in the world for these last two years, I plan to keep a close watch on things and see what happens in the future.

Translated by Christopher Stephens

© 2022 Maha Harada